Learning to read financial documents is one thing, but learning to use them as tools to guide the business and ultimately communicate clearly to 100+ investors has shown me just how nuanced our non-GAAP startup companies can be. In this post I’ll walk through the three phases of financial indicators in startups, and point out some common misunderstandings. I hope this will help founders and investors clarify what they mean when they talk about money, and I’ve used my company’s financials to give you real examples.

Key Financial Indicators

All three indicators are important, but emphasis shifts depending on stage:

Cash

In the beginning, cash is all that matters because it is the lifeblood of the company. It pays the team, rents the apartment you work out of, gets super-fast Internet access and a lot of snacks from Costco. It’s the printout from the ATM at the Mountain View Safeway that has two commas in it, and you dance around for a few minutes before reality sets in: the timer has started.

Managing the cash balance of the company as the most significant high-level financial indicator makes sense in the early days. You take the total bank balance you have, and divide it by how much you spent this month, and that tells you roughly how many months you have left before you run out of money. Maybe you take it one step further and make a simple forecast showing estimated hires and an estimated monthly rent when you move into a real office, but it’s still very simple.

Cash: Net Burn Rate

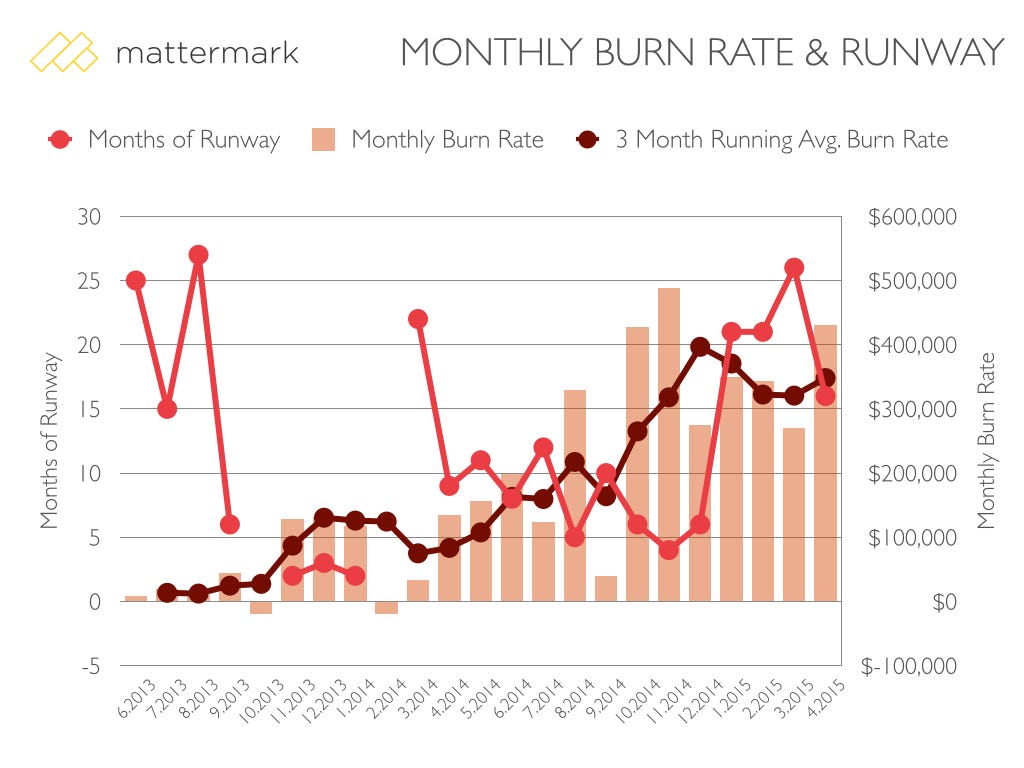

After coming so close to death when we shut down Referly and re-launched the company, we managed Mattermark’s accounting on a cash basis until the end of 2014. This graph shows our burn rate and months of runway:

Each month, we look at the change to our bank balance and ask, “was it greater or less than $400K? And if it was greater, why?”

We raised $6.5M in our Series A, which we just started spending. As I’ve shared previously, we’re sticking to a net burn rate of $400K per month which means in 12 months we should see our bank balance decrease by $4.8M ($400K x 12 months). Another way to think about raising this funding is that we bought 16.25 ($6.5M / $400K) of runway with 25% of the company.

So Mattermark gets to spend $400K a month, right? WRONG.

If we collect $1M in cash this month, we can spend $1.4M this month and we’ll have a net burn rate of $400K. If we collect $200K in cash this month, we can spend $600K and have a net burn rate of $400K. While spending $1.4M a month might sound irresponsible if you’ve been reading the news about startup burn rates, in the $1.4M scenario the company is covering 71% of expenses with cash from operations. In the $600K expense scenario, the company is covering only 33%.

As long as revenues are growing, burning $400K a month becomes less and less risky over time. Which brings us to our next phase of money: Run Rate.

Run Rate (ARR vs. ARR)

When we started out we were focused on cash because we didn’t have revenue, but as soon as we had revenue growing it was all that mattered. As a newly minted SaaS CEO I diligently studied SaaS metrics, and I was surprised to discover that run rate has different meanings depending on who you’r talking to, and your business model:

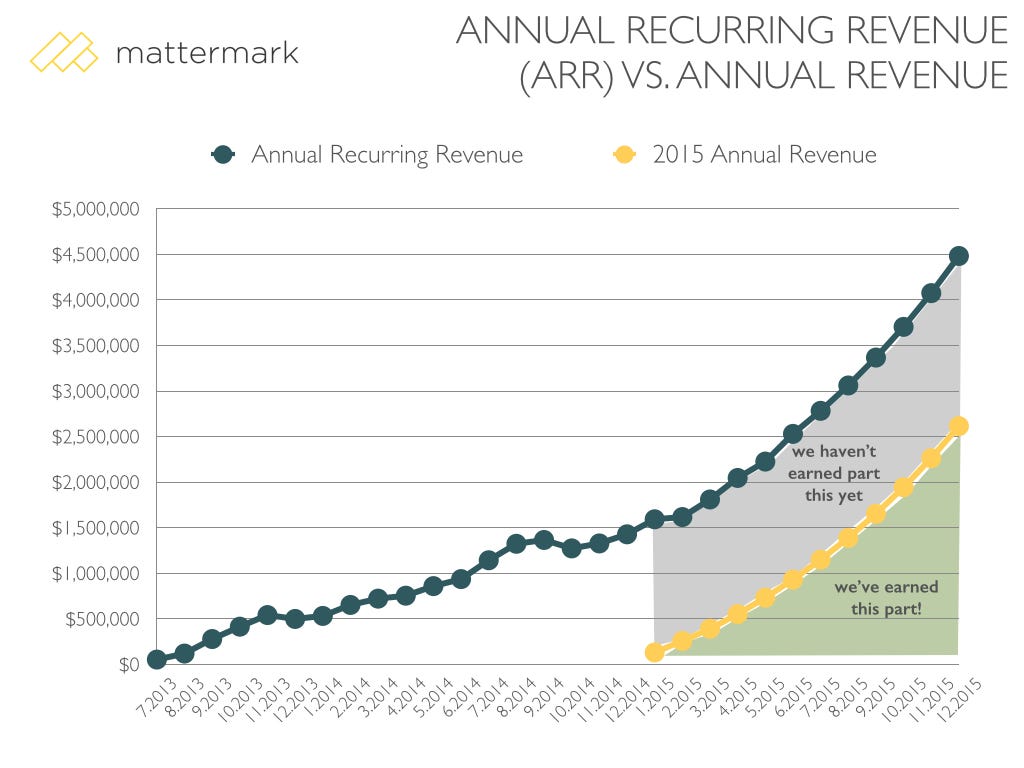

- Annualized Run Rate (ARR) — This metric extrapolates future performance of the company based on the latest results. Using this metric, a true statement about Mattermark would be: “our Q1 2015 quarter puts us at $1.57 Million run rate”. How did I get that number? I took the $392K of revenue earned in Q1 and multiplied it by 4 to get an annualized number.

- Annually Recurring Revenue (ARR) — With the rise of SaaS, recurring revenue has become more common. Recurring means there’s a subscription in place and the customer is charged on an ongoing basis, rather than a one-time purchase. E-commerce companies rarely have recurring revenue (exceptions: Amazon Prime and Le Tote) though they may be able to model the rate and value of return purchasers. In this case, a true statement about Mattermark would be: “at the end of Q1, our annually recurring revenue was $1.81 Million”. How did I get that number? I took the annual contract value of all existing subscriptions as of 3/31/15.

So far, these two numbers aren’t that different. Annual recurring revenue is 15% higher than annual run rate, based on Q1 performance. Here’s the problem though: I’ve been giving our investors guidance with a goal to achieve $4.5 Million in annually recurring revenue by the end of 2015. And I’ve told them we are only slightly (-3.2%) behind target.

So Mattermark is going to generate $4.5M in revenue for 2015? WRONG.

Based on our forecast, Mattermark will generate $2.6 Million in revenue for 2015 (a nice 147% increase from $1.05M in 2014) if we hit our goals.

The reason for the difference is important: we collect revenue for the entire annual contract up front for about 50% of our customers, but we made an important change at the beginning of 2015 and switched to accrual accounting. We now recognize revenue as it is earned, rather than when it is paid to the company.

That means if we sign up a customer for an annual contract and collect $12,000 from them on December 1st, 2015 only $1,000 of that money is attributed to 2015 revenue. The rest is unearned for 2015, and will be spread out over the next 11 months in 2016.

To illustrate the point again about why this can get confusing, consider the Annualized Run Rate metric above. Our forecast calls for $962K of revenue in Q4 of 2015, which would give us an annualized run rate of $3.85 Million ($962K x 4). All these statements are true, but which ones are right? Which ones should be communicated from founders to investors? Which should be used in fundraising to set valuations (i.e. multiplied by public market multiple for your specific sector)?

Therein lies the rub.

Revenue

In June 2015, the Wall Street Journal published “Tech Startups Woo Investors With Unconventional Financial Metrics — but Do Numbers Add Up?”, using statements from Hortonworks’ CEO to set the stage in the opening paragraph.

Chief Executive Rob Bearden forecast in March 2014 that the software firm would have a “strong $100 million run rate” by year-end. But the number looked a lot smaller after Hortonworks went public and then reported financial results: just $46 million in revenue last year.

Can you see how this confusion might have happened? As we’ve explored, run rate is not the same thing as revenue.

Deferred Revenue

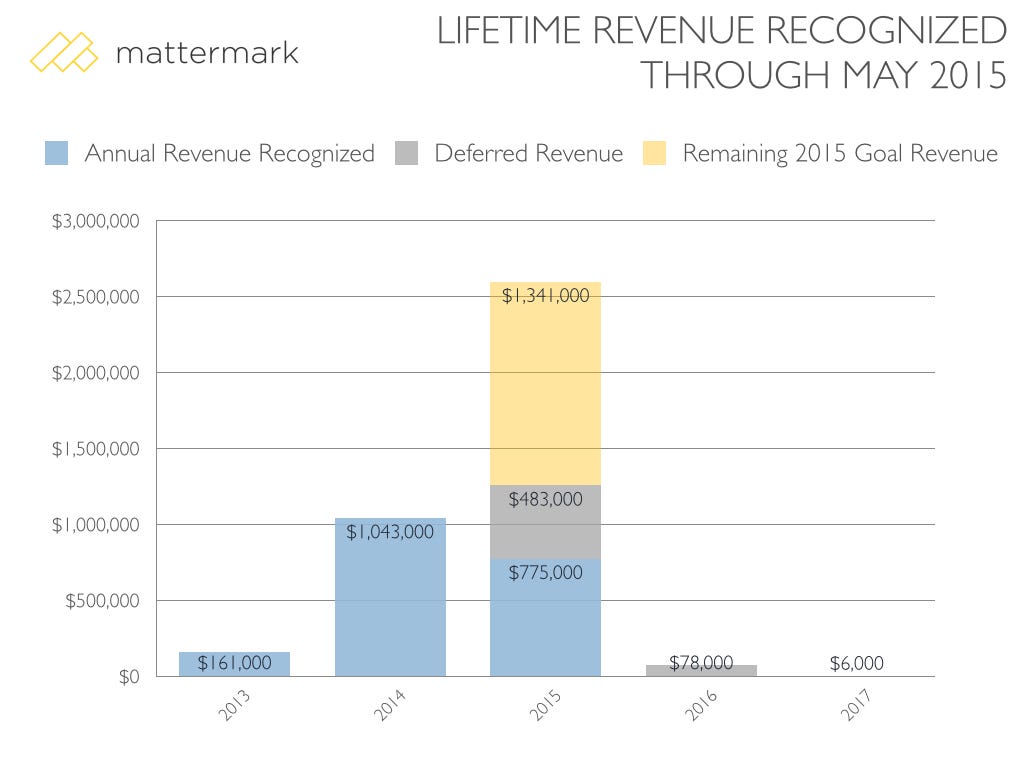

Earlier in this post I explained Mattermark’s year-end run rate will be $4.5M but our revenues for calendar 2015 will be $2.6M. Revenue for calendar 2015 will be only 58% of our year-end annual recurring revenue, and that’s great — because it means we’re growing! As the article goes on to explain:

It turns out that Mr. Bearden wasn’t talking about revenue, though he didn’t say so at the time. The Santa Clara, Calif., company now says the $100 million target was for “billings,” a gauge of future business that isn’t part of generally accepted accounting principles.

Right now we have ~$500K of revenue whose recognition is deferred between next month all the way out to November 2017. I love love looooove deferred revenue, because it’s cash we can use now. It’s non-dilutive financing for operations. It’s great! But it can be difficult to communicate, as the Hortonworks CEO found out.

What I didn’t like about this article was the suggestion that we’re doing something shady in reporting these numbers and providing this kind of guidance. If anything “billings”, future contract revenue, annual recurring revenue or whatever you want to call it is a valuable aspect of SaaS businesses that should be shared with investors as it helps create a more complete picture for why a company commands the price it does in the public market. These aren’t wishes and hopes, they’re numbers derived from real contracts signed with real customers.

Annual Recurring Revenue of a growing company will always be greater than annual revenue of the current calendar year, and investors who think this is misleading fundamentally do not understand how SaaS revenue works.

Revenue Multiples

Going back to our previous analysis, we had several different numbers we could use to offer guidance for Mattermark revenue in 2015: $1.57 Million annualized run rate based on Q1 performance, $1.81 Million based on annual recurring revenue at the end of Q1, $4.5 Million projected annual recurring revenue at the end of 2015, $2.6 Million forecasted revenue earned in calendar 2015, $3.85 Million annualized run rate based on forecasted Q4 2015 performance. All true statements, but which are the right metrics.

Choices choices.

How do we figure out what Mattermark is worth at the end of 2015? Let’s assume that Brad had a solid valuation model going into our Series A round. Mattermark was valued at $18.5 Million pre-money at $1.5M annual recurring revenue. That’s 12.3x annual recurring revenue, which lines up with the higher end of the range for SaaS company ARR multiples on exit.

If we assume 12.3x annual recurring revenue multiple holds steady, at the end of 2015 we would multiply $4.5M annually recurring revenue x 12.3 = $55.5M, which is 3x the original valuation on the round… a nice markup for our investor, and a healthy position for the company (which conveniently will have 6 months of runway at this point) to consider raising a $7-14M Series B (which would mean selling 10-20% of the company).

It’s almost like we planned it this way.

Of course growing slower and other exogenous factors (markets, multiples etc.) could change everything in this projection of the future, but it at least checks out as rational progression.

What About Profit?

You might be wondering why I didn’t include profitability as one of the phases. It is important, and can happen anywhere along the way depending on choices the company makes about how much to spend and when to pursue break even. As companies grow and mature, the distance from negative to cash flow break-even becomes a smaller percentage of revenue, increasing the company’s flexibility to decide to be profitable.

Profitability (or lack thereof) is a choice. Burn is one of the few things entirely within the company’s control.

Generally, I think controlling expenses is a lot easier than figuring out how to make more money. So when you do find a way to make money, you should leverage it like it’s an unfair advantage that could end at any time. In a market where capital is available to support rapid growth to claim a market, startups are operating a breakneck speed to claim it!

When the Bear Market Comes

Brad asked me 6 questions via email when I pitched him our Series A back in October 2014. The 6th one was: “Right now we are in a bull market. What happens when things reverse / we go into a bear market?”

My answer: Report on every minute of it with data. Longer contracts. Avoid selling to startups or SMBs, or businesses whose customers are startups or SMBs. Sell a huge library of one-off research reports to customers who can’t get budget for an analyst and/or tools. Cut expenses, hunker down and become profitable so we can control when/how we fund the company and choose our rate of growth into the future.

Still sounds like a pretty good downturn plan to me.